Leone Da Modena’s Manuals for the Dying

Avriel Bar-Levav

The structured mourning rituals of the Jews, such as the shiva with its specific demands on the mourners and their visitors, or saying kaddish, are quite known. Far less well-known is the existence of detailed rituals for people who are dying. Such rituals were created and printed in book form during the 16th and 17th centuries, first in Italy and then all around the Jewish world. These manuals formed a new genre in Jewish traditional literature–“books for the sick and the dying”–and tell us something about the ways in which modernity both threatened and lent new forms of expression to Jewish identity.

The herald of the new genre was a booklet of 18 small pages composed by the colorful rabbi and prolific writer Leone Modena (1571-1648), which was published in Venice in 1619. Modena named this booklet Balm for the Soul and Cure for the Bones.

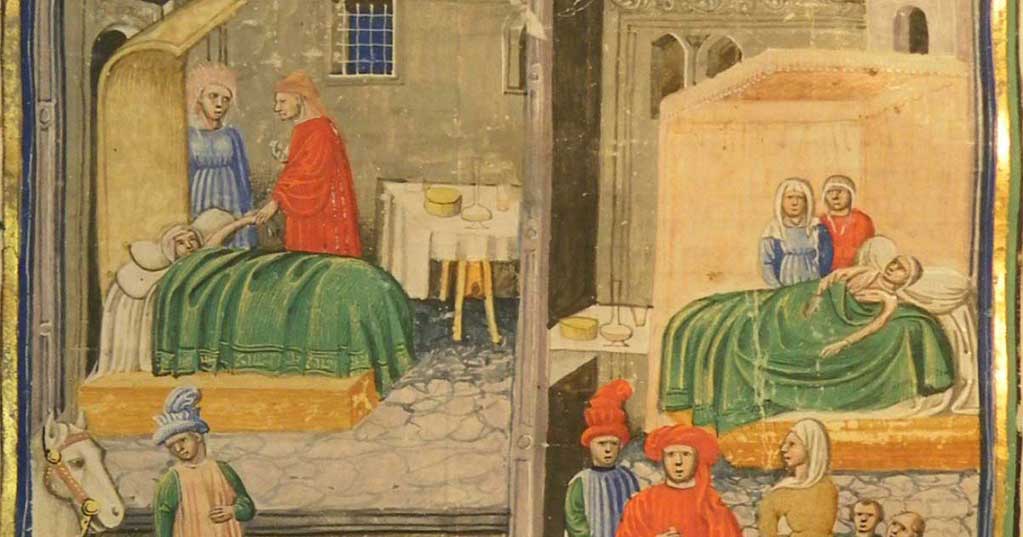

He wrote it (or actually compiled it, since he also used earlier sources) at the request of the governors of the Venice Ashkenazi burial society, who in their introduction to the work complained about the lack of a prescribed Jewish death ritual. Moreover, they say, “when it is the turn of one of the members of our society to go and watch over the sick person, and to stand by him as is our custom, we do not have a ritual of what to recite and converse in order to escort the soul of this person when he is dying, and gives his soul back to God who granted it.” That is, the institution of the burial society (hevra kadisha) existed before the existence of the actual ritual it was to perform around the deathbed.

The governors of the society asked Modena to fill the gap for the benefit of both the dying and the members of the society surrounding them. The ritual he suggested includes, inter alia, an alphabetical confession of sin, some Psalms, a concise credo, and a prayer for health.

But it was another book that gave real impetus to the new genre. This was Ma’avar Yabbok, written by a young nephew of Leon Modena, Aaron Berechia Modena, and published in Mantua in 1626. The phrase Ma’avar Yabbok, the Yabbok passage or ford, refers to the place where Jacob passed across Jordan River (Genesis 32:23). It would soon come to stand for the passage from life to death as structured by the rituals prescribed in this book and its many later digests and epitomes.

Ma’avar Yabbok itself is quite a voluminous work, with 112 chapters (112 being the numerical equivalent of the Hebrew letters comprising the word Yabbok).

Only one of the chapters is dedicated to a ritual for the dying, the rest being packed with deep theoretical discussions related to death and other topics, composed in a dense and erudite traditional style. The many short booklets following it bear the title Kitzur (abbreviated) Ma’avar Yabbok” or a ritual for the dying, the rest being packed with deep theoretical discussions related to death and other topics, composed in a dense and erudite traditional style. The many short booklets following it bear the title Kitzur (abbreviated) Ma’avar Yabbok.”

Through the 18th century, dozens of editions of manuals for the dying were printed all around the Jewish world, east and west, some with translations into Yiddish and other languages. Only at the outbreak of modernity, in the 19th century, did the phenomenon almost cease. What is the meaning of this efflorescence and subsequently its almost total disappearance?

The attempt to mold the period of death was part of a general process that Jewish society underwent during the early modern period, a process that could be called the ritualization of Jewish life and that included many other aspects such as meals, the Sabbath, and more. Was this an effort on the part of a traditional society that sensed its near-disintegration and strove to tighten its grasp over the lives of believers?

As for the subsequent disappearance of the structured death, one reason is that death no longer occurs in the private spaces where such rituals could be preformed.

The scene of death has been mostly moved to the hospital, where only professionals are allowed near the dying person, professionals who bend every effort to fight off death and save their patient’s life. In modern times, death is often considered to mark the failure of such medical efforts, rather than as the destiny of all living things. This

attempt to conquer and deny death is symbolized in the rejection of the religious shaping of the time of dying and of death.

Dr. Avriel Bar-Levav is a senior lecturer at the department of history, philosophy and Jewish studies at the Open University of Israel, and the editor of Pe’amim: Journal for the Study of Eastern Jewry. His email is avribar@openu.ac.il. This essay, under the title “Jewish Manuals for the Dying in the Early Modern Period,” first appeared in Sh’ma, 34/603 (September 2003), and is reprinted by permission.