Prescribing Love: Italian Jewish Physicians Writing on Lovesickness

Michal Altbauer-Rudnik

“… for love is strong as death, and wrath bitter as the underworld: its coals are coals of fire; violent are its flames.” (The Song of Songs, 8:6)

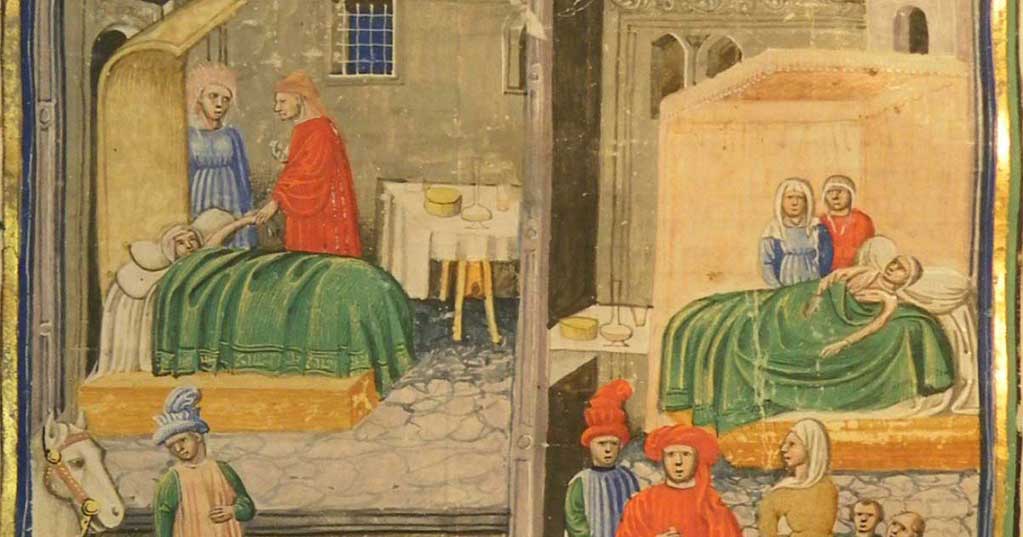

Although the present study focuses on the early modern period, it is worthwhile to consider how the presentation of love-related pathologies had produced a specific medical diagnosis in earlier periods, since many of the features of this presentation did not change in later generations.5 As with all diseases, etiological explanations of melancholy were based upon the humoral theory, according to which the human body is made up of four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm), each characterized by different qualities of heat and moisture, with good health being the result of an optimal balance among the four. The earliest and most ordered discussions of the subject of lovesickness can be found in the writings of Aretaeus the Cappadocian and of Galen, both of whom described the disease as a depressive illness whose symptoms, but not its etiology, match those of melancholy.

According to the Hippocratic writings, the symptoms associated with melancholy include depression, fear, eating disorders, insomnia, irritability and restlessness. But whereas in the case of melancholy, the depression and fear have no apparent cause, in the case of lovesickness, the cause is an obvious one – i.e., the separation from the object of love. While the cause of melancholy was understood to be both physiological and natural (an excess of black bile), the cause of lovesickness was understood as being primarily emotional.

The medical view taken of lovesickness during the middle ages was not dramatically different. Oribasius, Alexander of Tralles and Paul of Aegina were among those who described the lovesick as displaying the symptoms of melancholy. The contribution of Arab medicine in the ninth and tenth centuries regarding this subject was to consolidate the symptoms into a specific diagnosis of love melancholy. The clinical picture, however, remained unchanged. Although the conceptual contributions of medieval literature regarding courtly love and of Italian Renaissance treatises on love will not be discussed here, it is important to mention their immense influence on contemporary medical writing, as well as the blurring of the boundaries between philosophical discussion and medical analysis which characterized the medical literature on this subject during these periods.

The volume of medical literature concerning lovesickness increased dramatically from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century, with physicians (mainly but not exclusively French) such as Valleriola [1588], du Laurens [1597], Aubrey [1599], Platter [1602], de Veyries [1609], or Sennert [1611], devoting dozens and sometimes hundreds of pages to its specific diagnosis and prognosis, but most of all to its etiology and therapy.

Predisposition to the disease was linked to the dominance of blood (a sanguine tendency) which meant that the body was inclined to moisture and heat.

This high level of blood in the human body was believed to produce a natural inclination to all the passions, especially erotic love. However, the understanding was that a natural inclination of the body to melancholy could not, in itself, bring about love melancholy. Sanguinity would upset the humoral balance of the body, but could not, by itself, cause any agony or physical distress. Thus, sanguinity was described as the contagion stage. The presence of a beautiful object which attracts the individual’s eye would, of course, be necessary to bring about the actual illness.

Melancholy, it was understood, took over only in the second stage of the disease, when for some reason the person was separated from his or her beloved and could not consummate his or her love. The unfulfilled love would then dry and cool the body, causing dominance of the black melancholy bile. Excessive mental action, due to constant meditation on the object of love, would exacerbate the dominance of melancholy, while the emotional turmoil and the symptoms of melancholy would promote the spread of black bile through the body, and would thus intensify the person’s despair and physical suffering. Ferrand lists the symptoms briefly as follows (before providing details of each of them):

Pale and wan complexion, joined by a slow fever …

palpitations of the heart, swelling of the face, depraved

appetite, a sense of grief, sighing, causeless tears,

irresistible hunger, raging thirst, oppression, suffocation,

insomnia, headaches, melancholy, epilepsy, madness,

uterine fury, satyriasis, and other pernicious symptoms …6