The history of the Jews in Marche dates back more than a thousand years. Land records as early as 967 show that Jews were owners of vineyards and olive groves. Documents dating from that year record a land sale by Peter, bishop of Ravenna, to Elijah “The Righteous”. Over the centuries, this region had at least thirty well-documented Jewish communities.

By the 1200s, the city of Recanati, located between Ancona and Senigallia, had a reputation as a seat of Jewish learning. Jewish communities in Fano and Pesaro were flourishing in 1214, as mentioned in the “Consulta” of Rabbi Eliezer Ben Joel Ha Levi. The earthquake of 1279 destroyed the city of Ancona. Held responsible for the cataclysm, many Jews were slaughtered. A special prayer is still recited by Ancona Jews on the 9th of April. The prayer for the destruction of the Second Temple also mentions the burning of the Jews of Ancona and the victims of the Shoah.

In the 1300s, the port city of Senigallia was buzzing with lucrative Jewish businesses. The Jewish scholar, Master Daniel, arrived in Urbino from Viterbo to open a bank and establish trade. Other thriving cities include the sea port of Pesaro, and Fermo, a city mentioned by the great poet Immanuel ben Solomon of Rome, who found hospitality there in the house of a wealthy merchant. His great work, the “Mahbarot” was extensively edited in Fermo.

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1497, waves of Sephardic refugees began to arrive, settling in Ancona and the other port cities. Shortly after, they were followed by Jews from Sicily and the south of Italy who had formerly lived in the Kingdom of Naples. By the 1540s, Pope Paul III had invited merchants from the Levant to settle in Ancona, regardless of their religion. He encouraged the settlement of Jews and crypto-Jews promising protection from the Inquisition. Approximately 100 Portuguese crypto-Jewish families settled in Ancona at this time. Since trade was the life blood of the Adriatic port cities, certain modifications enabling the Jews to continue to trade with Turkey and the Levant were introduced in order to avert a commercial crisis. At this point in Marche, the Jews were divided between those who followed the ancient Italian rite and those following the Levantine or Sephardic rite.

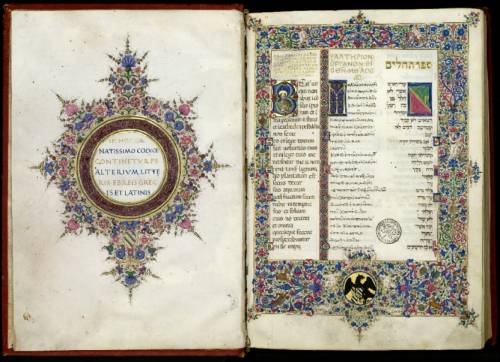

1. Villa Imperiale in Pesaro, Girolamo Genga (Urbino 1476-Casteldelci 1551), Biblioteca Oliveriana. 2. Bernardino Pinturicchio, Aeneas Piccolomini Arrives in Ancona, fresco, 1502-08, Piccolomini Library, 3. Hebrew psalter, Library of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

In 1555, the situation changed dramatically for the Jews. Pope Paul IV adopted anti-Jewish measures in the Papal States, which included Marche. The Jews of Ancona were forced to live in a ghetto, prohibited from owning property, and restricted to trading in secondhand clothing. Some Jewish families managed to escape north to Senigallia, Pesaro and Ferrara. Twenty-five crypto-Jews were burned at the stake in Ancona in 1555. Following these events, Dona Gracia Nasi, a rich Jewish merchant, organized a boycott of the port of Ancona. Historians view her actions as the first attempt by Jews to utilize economic power as a weapon against persecutors. In 1569, when Pope Pius V expelled the Jews from the Papal States, Ancona and Rome were the only cities in which they where permitted to reside, due to their usefulness in the trade with the Levant.

When, in 1633, with the death of the last Duke of Urbino, the duchy passed to the Church, ghettos were established in Urbino, Pesaro and Senigallia. Many towns and cities from which Jews had left, petitioned the Pope requesting the return of Jewish bankers to “help the needs of the poor and the emerging wool industry”.

In 1797, the arrival of the French Army led to the opening of the ghettos. It was a short-lived joy. After the departure of the French, repression was fierce particularly in Urbino, Pesaro and Senigallia. Hordes of Sanfedists, at the cry of “Viva Maria” stormed the streets of the ghettos, looting homes, destroying the insides of the synagogue and brutally slaughtering thirteen Jews, including three women. Dozens of wounded and survivors found shelter on a ship sent by the Jews of Ancona.

In the nineteenth century, the Jews of Marche contributed soldiers and large sums to the cause of the Risorgimento. Through funding from companies such as Moisé Salmoni & C. and Sanson Vivanti, the Jews also supported the underground activities of the secret societies Carboneria and Giovane Italia. Yet their participation in the Risorgimento had dire consequences. In 1860, by order of the Pontific General Lamorcière, just before the unification of Italy, the Spanish-Levantine synagogue of Ancona was destroyed.

The Italian synagogue of Ancona followed the same fate in 1932, when it was demolished by the Fascist authorities under the pretext of the construction of Via Stamura. Of the 157 Jews of Ancona deported to Germany during the war, only 15 returned.

The Jews of Ancona at Beit Hatefutsot

Toponomy and Jewish last names

Marche is the Italian region that originated the largest number of Jewish last names. These were the “place of provenance” names, adopted by families to distinguish themselves from those of more recent immigration. In 1569, following Pope Pius V’s expulsion of Jews from all of the Papal States, with the exception of Ancona, many took the name of their town of origin as their last name. Today many Jewish Italian last names bear testimony to the Jewish ancient presence in the towns and cities of Marche, among others: Ascoli, Barchi, Belforte, Cagli, Camerino, Cingoli, Da Fano, D’Ancona, Della Pergola, D’Urbino, Fano, Iesi, Macerata, Mondolfo, Mondolfi, Moresco, Moreschi, Osimo, Pesaro, Pergola, Recanati, Senigallia, Senigaglia, Tolentino, Urbino, Urbini.

Trade and professions

Jews in Marche were renowned for the currieries and tanneries, where they developed their own techniques to preserve and decorate leather.

They had brought with them expertise in ceramic arts from Spain and silk processing (thus the last names Seta and Della Seta) from Sicily. Most towns and villages along the rivers had at least one Jewish family of dyers, originating the last name Tintori. By the end of the 1400, many Jews were attracted by the fascinating new art of printing. Abraham Gershon Soncino, of the great Jewish printing family, was active in Pesaro. Jewish high quality printing presses were established also in Fano, Pesaro and Ancona. Their output was unfortunately burned in great part in 1553, by edict of Pope Julius III. The same Pope forbade Talmud printing, resulting in about 12,000 copies being destroyed.

Last names like Orefice and Sarto (Goldsmith and Taylor) are reminders of the trades Jews once mastered and taught to Christian apprentices. Later, with the establishment of guilds, each under the aegis of a saint, Jews were excluded and relegated to ‘strazzeri,’ or peddlers. They were allowed to keep the practices of medicine and money lending, regulated by special laws, as well as taxes and licensing contracts.

The tradition of Jews in medicine hails back to Maimonides and the Arab world. Medical licensing was common among Jews and not only in Marche. Frederick II had invited Jewish physicians to the renowned Salerno School of Medicine and, with very few exceptions, the Pope’s personal doctors were Jewish. One of Marche’s most famous physicians, Elijah Sabato, was from the city of Fermo. He was called to Rome in 1405 as personal physician to Pope Innocent VII. In 1410, he became chief physician for Martin V and later moved to England to the court of King Henry IV. He was appointed chief physician by Pope Eugene IV, later the Viscontis, in Milan, and finally the Estes, in Ferrara.

Emulating the higher clergy, the aristocracy also preferred Jewish physicians, a circumstance that would later contribute to resentments against the Jews. Their medical knowledge was later linked to accusations of ritual murder.

Thanks to their entrepreneurship and mobility, the Jews made Marche into one of the most active trade centers in the Mediterranean, often raising concerns of rivalry with powerful the Venetian Republic.