Jews lived in Apulia from ancient Roman times until 1541, when they were banished from all of Southern Italy. They arrived after the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD, when emperor Tito brought back 5,000 Jewish war prisoners, who subsequently settled in and around Taranto.

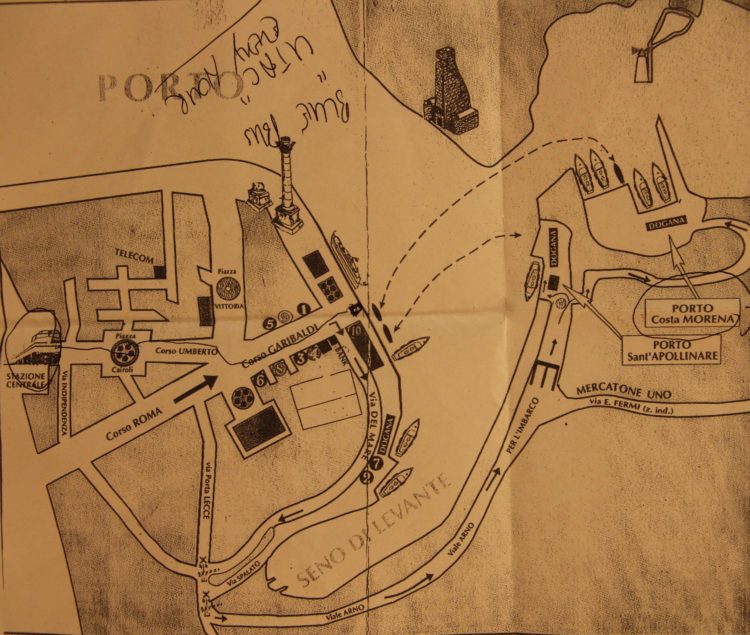

The records are sparse over the next two centuries, though we know that the great historian Josephus wrote his major works at the imperial court in Rome during this time. By the third century, Jewish funeral inscriptions indicate definite settlements in the Southern cities of Bari, Oria, Capua, Otranto, Taranto, and above all, Venosa. These were important stops along the main trade route from Rome to the Eastern Mediterranean and Byzantium. The Via Appia (or the Appian Way), which linked Rome to the southern tip in Brindisi, the main port city on the Adriatic, ran through Capua, Venosa, Taranto, and Oria, and was scattered with Jewish settlements. The Jews on this route formed essential links in the chain of international trade, lived on friendly terms with the rest of the population, and suffered equally with their Christian neighbors from the Saracen and Northern invasions.

Archeological findings from the early centuries AD point to Jewish presence in Apulia under the Roman Empire.

By the ninth century, local Jewry had acquired its own unique profile, known to us through poetic and liturgical texts produced in Oria and Taranto, as well as the legacy of the rabbinical schools of Otranto, Bari and Trani, which flourished in the 13th century.

In the 12th century, French Tosafist Jacob ben Meir recognized Apulia as a preeminent center of Jewish learning. Rabbinical scholars of Apulia in the 13th century include Isaiah ben Mali (the Elder) of Trani, his grandson Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani, Solomon ben ha-Yatom, and Abraham de Balmes.

In this sense Apulian Judaism can be considered as one of the oldest testimonies of the Western European Diaspora.

In the Middle Ages, Apulian Jewry lived through alternating periods of tolerance and persecution, especially after part of the region fell under the Kingdom of Naples. In spite of uncertainty, local Jewry established ties with cultural and economic centers along the Mediterranean and in the Balkans. A significant population of Iberian exiles settled in Apulia after the expulsion of 1492.

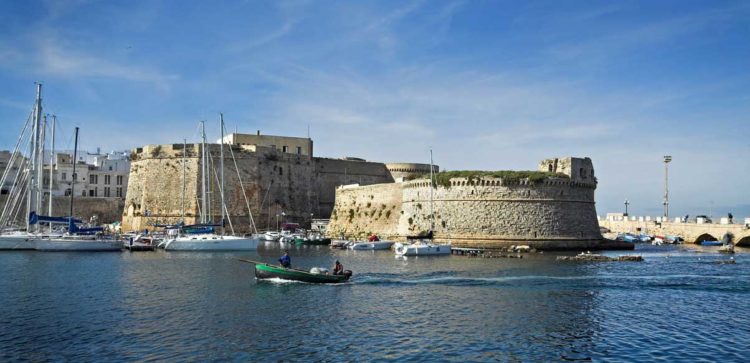

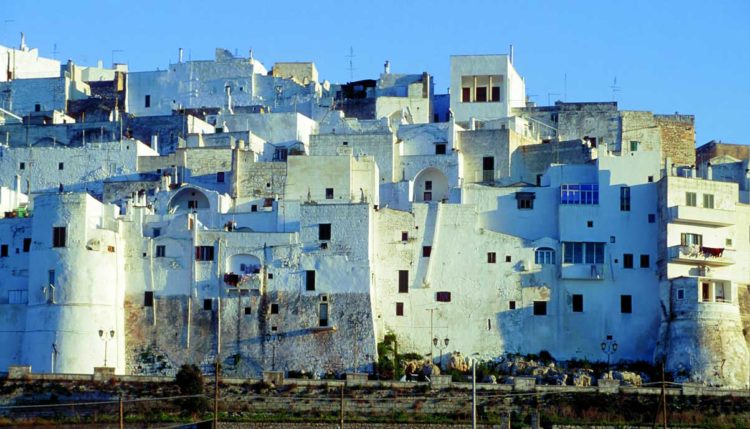

Apulia surpasses every other area in Europe – except possibly Spain – as a place to see original medieval Jewish buildings and artifacts. The medieval Jewish quarter in Trani is unique in its intact state. Nowhere outside of museums are there Jewish tombstones from before the tenth century like in Trani and Venosa; nowhere other than in Rome are there Jewish catacombs like the ones in Venosa. And in cities like Oria and Taranto there still exist significant traces of the former Jewish medieval Giudecche.

The edicts of 1510 and 1541 abruptly uprooted the community and its institutions. Its traces remained in the cultural fabric of the region through the conversos, who were assimilated into the local population. After their final expulsion, Apulian Jews settled mostly in Corfù, Arta and Salonika.

In the 19th century small groups of Jewish traders settled on the Adriatic coast without creating a formal community.

During the aftermath of World War II, the Allies established several transit and DP camps in Apulia. These became temporary homes to many Jewish refugees from Northern Europe, as well as operation centers for the Aliah Beth.

Episodes of mass conversion spurred a renaissance of Jewish life in Apulia during the 20th century. Most notable is the striking conversion of the San Nicandresi or Sabbatini in the 1930′s and 1940′s. More recently, we are witnessing the re-birth of a new Jewish community in Trani, a phenomenon unique in Europe.