Paggi and Bemporad

Alessandro Paggi came from a Jewish family from Siena and moved to Florence in 1840. There, he started a small printing and publishing business supported by the sale of stationery items. A few years later his brother Felice joined the company which was renamed “Libreria Editrice Felice Paggi.” Their first titles included medical books from the Risorgimento era. Later it focused on school and children books.

The Libreria Editrice Paggi published six hundred and seventy one titles divided into three series: “Biblioteca Italiana” (1851), “Biblioteca ricreativa” (1881) and “Biblioteca scolastica” (1860).

The publishing company remained a family business. In 1889, Felice Paggi signed over the company to his nephew Roberto Bemporad and his son Enrico, who had invested in the firm since 1862. The new name became “Roberto Bemporad e Figlio Cessionari della Libreria Editrice Felice Paggi”.

After his father’s untimely death in 1891, and the death of his grandfather in 1893, Enrico Bemporad found himself at the head of the publishing house while only in his early twenties. He had started working at his grandfather’s bookstore after completing technical studies.

no images were found

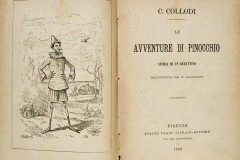

His first titles with the new imprint date from 1889 and are mostly school books re-issued from the Paggi catalog. Bemporad relied on the collaboration of some of Paggi’s authors and editors including Pietro Thouar, Ida Baccini and Carlo Lorenzini (Collodi) whose The Adventures of Pinocchio he had published. Through Pinocchio, Giamburrasca and Pellegrino Artusi’s legendary cookbook “La Scienza in Cucina,” Bemporad captured and forged an essential aspect of Italian culture.

Youth

In 1889, the Bemporad print-shop released eight titles and sixteen more in 1893. Between the years 1897 and 1898, the Bemporad’s catalogue reached forty titles. After launching “Biblioteca scolastica,” Enrico Bemporad gave further impulse to the production by introducing the stereotype machine, allowing for higher runs of the “Collana azzurra”.

Children’s literature became a driving force for the publishing house at a time when information and accessible readings were thought to be key to the development of the new country.

The collection of youth adventure novels (1901) and the “Biblioteca Bemporad per Ragazzi”(1915) were designed to offer to a wide audience the possibility to create home and school libraries. Bemporad also wanted to expose youth to international authors. He published works by Dickens, Andersen, Verne, De Foe, Dumas, Hoffmann, Grimm, Mark Twain, London, Stevenson and Alcott.

Starting in 1910 the “Collezione economica Bemporad”, and the “Nuova collezione economica Bemporad di racconti romanzi e avventure” offered novels, with illustrations and color jackets, at the modest price of 95 cents. They were sold in bookstores as well as news stands and train stations.

During the first two decades of the 1900s, Bemporad’s publishing continued to flourish. Between 1914 and 1925, the catalogue grew from sixty one to hundred and seven titles, featuring a great variety of genres and categories. The quality of publications was remarkable. In 1920, Bemporad took on the publication of books for the Royal Institute of Higher Education and released the first titles of a new series entitled “Grandi autori”. In 1921, Bemporad published the national edition of Dante’s works for the Italian Dante Society.

Enrico Bemporad, along with Attilio Vallecchi, was among the founders of the “International Book Fair,” which was first held in 1924 at the Art Institute of Florence, Porta Romana. In 1927, Bemporad, together with Gaspero Barbera and Ettore Salani, was part of the organizing committee of the Florentine section of the fascist union of publishers.

In the meantime, the house attracted important authors in Italian literature including Luigi Pirandello and Giovanni Verga. The house also took on popular literature, including the controversial Guido da Verona, who is considered to be the father of modern Italian erotica and feuilleton novels. In 1906, Bemporad also began to publish the beloved youth author Emilio Salgari.

Although Bemporad was known for his loyalty to his authors, he also encountered some hostility, perhaps due to his many public roles in the publishing world. In 1928, he was accused of failing to fairly pay Emilio Salgari, who, stranded by debts, had committed suicide.

Decline

After 1925, the house faced a period of decline. Compounding losses from 1928 to 1930, in 1934, Bemporad was forced to take a mortgage from Monte dei Paschi di Siena and La Fondiaria.

A survey of the catalogue does not reveal the crisis until 1935, when the Bemporad printed only fifty seven titles compared to the hundred and sixteen of the previous year.

Another reason for the crisis was the dictatorship’s introduction, in 1928, of a unified elementary school text book, which challenged the mass production of children’s and young adult books that had flourished in liberal Italy. Bemporad’s production of school books was quickly reduced to less than half.

Enrico Bemporad was aligned with Fascism for most of his life. In 1927, he published the series “Quaderni fascisti” and in 1934, “Libri dell’ardimento,” as well as work by Lidio Cipriani, a popular champion of colonial racism.

A man born and educated in the 19th century, like many others in his field, Bemporad was perhaps seduced by the dictatorship’s initial support for the publishing industry, which became the heart of the propaganda machine. The promise of efficiency and progress, as well as the assumption that the values of liberal Italy were still operative, allowed a large sector of the cultural establishment to become complacent with the regime. Not enough research has been conducted to explain how publishers managed to navigate the hardship of censorship and the restriction on foreign books, which they had to deal with on an ongoing basis.

The consequences of Fascist repression began to affect Enrico Bemporad and his publishing house as early as 1928, eroding the very intellectual fabric of his company. In 1938, the Racial Laws barred him from his job and forced him to sign his publishing house over to non-Jewish delegates. Bemporad died in 1944.

After World War II, Renato Giunti took over the company, and gave it the name of Bemporad Marzocco.