Women in the Torah

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini was born in Collegara, near Modena, on June 21, 1878 to Pellegrino and Marianna Nacmani. His father belonged to a well-to-do family of Jewish descent that, since the 18th century, had successfully conducted careers in the precious stone trade.

After completing his studies in Modena, he graduated in Law with a thesis on “A comparison between the women of the Torah and those of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. Historical and legal contribution to a rapprochement between the Aryan and the Semitic races”. Soon after, he joined the faculty of letters at the University of Rome, where he deepened his interest in overcoming barriers between people of different ethnic, religious, social and political background.

Formiggini was active in the international masonic association Corda Fratres. He married Emilia Santamaria, who became known for her research on the history of education. They moved to Bologna where, in 1907, he graduated in philosophy with a thesis entitled “The philosophy of laughter.”

In the convivial atmosphere of the University of Bologna, Formiggini conceived his publishing enterprise. With the participation of distinguished writers and professors from the universities of Bologna and Modena, Formiggini promoted the celebration of A. Tassoni’s Secchia Rapita, with a collection of unpublished sonnets and other humorous poems. This small pamphlet opened the way to what would become one of the most original publishing houses of the first decades of the 20th century.

His first real publication consisted of thirty “historical and literary studies” entitled Miscellanea Tassoniana (Modena 1908); Pascoli wrote the preface and took it upon himself to introduce the young publisher to the public.

This first success convinced Formiggini to continue. In 1908, in keeping with his interests and those of his wife’s, he began two series of studies: “Biblioteca di filosofia e pedagogia” and “Opuscoli di filosofia e di pedagogia”.

The small publishing house became an outlet for both positivism and spiritualism spurring lively debates and exchanges. However, many of the planned series were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, including the “Filosofi Italiani,” which never went beyond the first title, Bernardino Telesio’s De Rerum Naturae, published in three volumes. Formiggini managed to keep publishing his Rivista Filosofica(1909-1919) and the Rivista Pedagogica (1910-1912), thanks to his close relations with the academic circles. He also published the Proceedings of the Congress of the Italian Philosophical Society from 1908 to 1913.

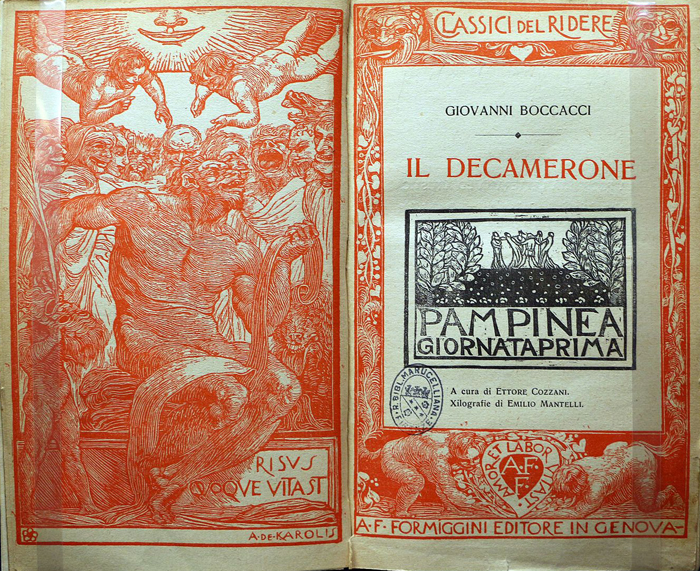

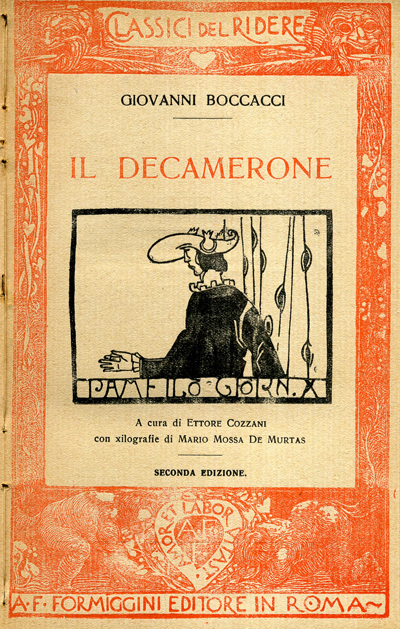

Two series from this period would leave a profound imprint on the house: ”Profili”, which between 1909 and 1938 featured 189 titles, and “Classici del riso” with 105 titles published between 1913 and 1938.

Books for All

“Profili” met the favor of a broad lay public interested in famous historical figures. The other series appealed to more sophisticated readers who, at a nominal cost, could acquire beautifully crafted volumes printed on parchment, adorned with original illustrations, and enriched with excellent bibliographical appendixes.

Formiggini soon launched the “Biblioteca filologica e letteraria,” which did not last for more than a year but presented some important titles. Much more successful was the series “Poeti italiani del XX secolo” that, between 1910 and 1938, became an outlet for writers and poets of the new generations.

After the first years in Modena, the publishing house moved to Genoa in 1911. Here, Formiggini launched “Calssici del riso” (Classics of laughter), featuring humor literature from every culture and age.

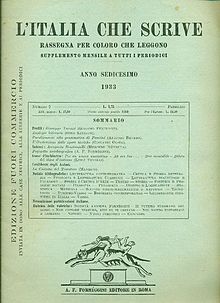

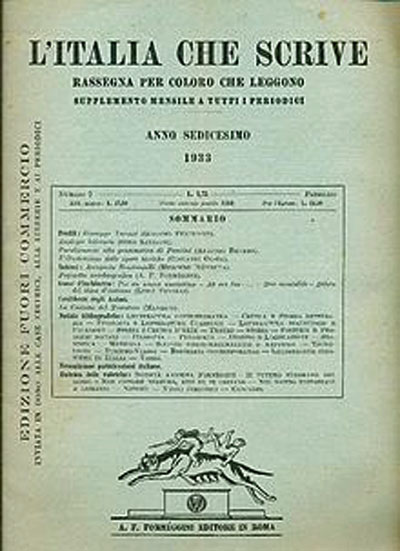

L'Italia che scrive

In 1915, Formiggini was drafted and his wife took on the firm. He returned home a year later due to illness and moved the press to Rome. In Rome, he founded a magazine that profoundly captured the spirit of post-unification: L’Italia che scrive, a rich bibliographical report meant to inform the general public about what was happening in the book world and help lift the cultural establishment from the post-war crisis.

He invited other publishers to join his effort, which he regarded as a collective initiative, but he did not receive much support. However, L’Italia che scrive became a success beyond expectation and ended up having a profound impact on cultural life in the 1920s and the 1930s.

In order to give the magazine a broader scope, Formiggini founded and financed the Institute for Book Propaganda in 1919, placing it under the honorary chairmanship of the Ministers of Education and Foreign Affairs and with a board of directors that included representatives from many political and cultural institutions.

In 1921, the Institute was transformed into the Leonardo Foundation which launched many initiatives, including a plan for an “Enciclopedia Italiana,” circulating libraries, as well as bibliographic guides for all fields of knowledge.

Both the Leonardo Foundation and L’Italia che scrive gained momentum and became well known among specialists, as well as the general public. In 1923, however, Formiggini’s vision to include a broader constituency and to support the publishing industry on a national level, began to clash with the ambitions of dictatorship.

The March on Leonardo

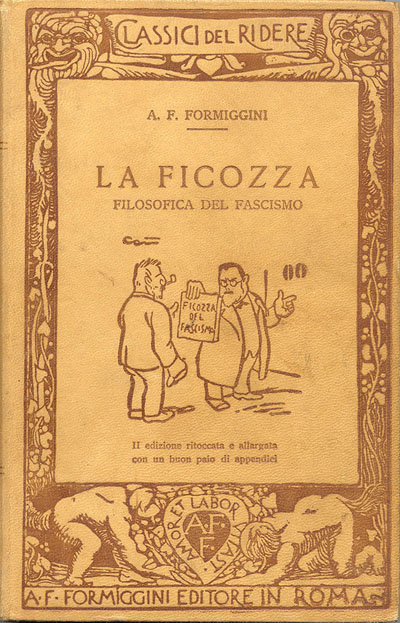

Mussolini had taken power a year earlier and sought to take direct control of all organisms of national propaganda. As Formiggini later explained in a political pamphlet, the then Minister of Education, Giovanni Gentile, had launched a “march on Leonardo,” ousting its founder and placing the institute under government control.

Formiggini returned to his publishing work trying to revive the theater series in which he had released Pirandello’s Liolà and relaunching some of his most successful series including “Profili” and “Classici del ridere”. He also began to publish a series of small volumes on world religions called “Apologie”. The idea was to defend all religions and make them acceptable to one another. Fourteen volumes came out under this umbrella. Ironically, this happened during the years leading up to the end of religious freedom in Italy, marked by the Lateran Pacts in 1929.

In 1927, he published Mussolini’s Battaglie giornalistiche. He also started two new series “Lettere d’amore” (1925-1938) and “Guide radio liriche” (1929-1936). Investing in publications that were closer to popular sensibility and current interests, Formiggini had hoped to lift the publishing house from a crisis that was slowly eroding his assets and sources of income.

Apologie

In 1938, after the promulgation of the Racial Laws, the Ministry of Culture demanded that publishing houses fill a form concerning non-Aryan employees. Formiggini’s company had become an limited liability corporation so as not to leave a trace of the Jewish name of its owner. He could no longer continue his work.

Angelo Fortunato Formaggini had dedicated his life to the circulation of knowledge and to infusing society with the values of tolerance and respect. He had this through books and culture.

On November 29, 1938 he ended his life, jumping from the tower of Modena, la Ghirlandina. The authorities were prohibited from circulating any kind of information about his death, as well as from holding a public funeral.