The first mention of Jews in Mantua dates from the 12th century, when Abraham ibn Ezra finished his grammatical work “Zahot”(1145) there. Apparently, he was in the city again in 1153. There are no further references to Jews in connection with Mantua until they are mentioned in the new statutes of the city at the end of the 13th century, when a large number seem to have lived there.

The noble Gonzaga family ruled in Mantua from 1328 until 1708; they also ruled the Monferrato area in Piedmont and Nevers in France, as well as several lesser fiefs in Italy and Europe. Under the Gonzagas, Mantua was a relative haven of religious and cultural tolerance and the Jewish community grew to reach 3,000 in 1610, when Jews constituted about 7.5% of the population. Jewish bankers were invited to start transactions in Mantua and its province, where some 50 Jewish settlements of varying sizes flourished, such as Bozzolo, Sabbioneta, Guastalla, Viadana, Revere, Sermide, and Ostiano.

Until the 19th century, the Jewish community of Mantua was the only important one in Lombardy. The Gonzagas treated the Jews relatively well for the times, by honoring their agreements, protecting Jewish merchants from the guilds and from physical violence. On the other hand, the Gonzagas periodically extorted money from the Jewish community by imposing special taxes on Jewish businesses. The Jews engaged in various trades and crafts: banking, jewelry, clothing, printing, and were also very involved in court life and culture.

There was an isolated case of blood libel in 1478 and rioting in 1495, after Duke Francesco Gonzaga’s victory at Fornovo against the French forces, resulting in the confiscation of the house of the banker Daniel Norsa and the erection of a church, Santa Maria della Vittoria on the site.

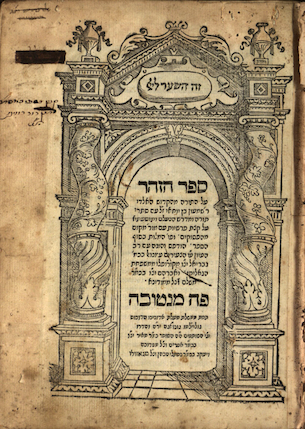

A Hebrew printing press was established in Mantua – the second largest in Italy after Venice – by the physician Abraham ben Solomon Conat and his wife Estellina.

The first edition of the Sefer haZohar Mantua, was printed in Mantua by the printer Ya’akov Ha-Cohen of Gazzuolo. Azaria dei Rossi (Mantua, 1513-1578), one of the great lights of Italian Jewry, a scholar and physician, published Me’or Einayim (Light for the Eyes). Using classical Greek, Latin, Christian and Jewish sources, he is the first since antiquity to deal with the Hellenistic-Jewish philosopher Philo. His critical method of analysis and refusal to accept rabbinic legend as literal truth resulted in the work being banned in many Jewish communities. The book was published by Joseph Shalit and Jacob b. Naphtali in Mantua from 1556 at Ruffinelli’s.

Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga decided that a ghetto should be established in the capital in 1602. This plan was started in 1610. The Mantuan community was the last of the large Italian communities to be confined to a ghetto and among those who did not object to the foundation of a ghetto.

In 1624, Salomone De Rossi, leading Jewish composer of the Renaissance, wrote a collection of synagogue choral compositions. It was the first Hebrew book to be printed with musical notations. De Rossi was one of a number of Italian Jewish court musicians; most of his secular music was not composed for Jewish audiences.

By 1761, there were 2,114 Jews living in the city. During the 18th century, the Jewish community of Mantua was one of the largest in Italy. When the duchy passed from the Gonzaga to the Austrian Empire in 1707, it was the largest community in Lombardy and together with Trieste and Gorizia one of the few Italian dominions of the Habsburgs.

Under the Habsburgs the situation of the Jews improved: between the 1770s and 1780s there were between 2100 and 2200 individuals within the city (8-10% of the entire city population).

Throughout the 18th century, Mantua continued to be an important centre of Jewish culture; there were 6 synagogues in the city, 3 Italian and 3 Ashkenazi, all with their own rabbis. At the beginning of the century, the famous rabbi Moshe Zacuto wrote on Kabbala, Halacha, poetry and drama, and there were others such as Leone Brielli and Solomon Basilea who published a section of the Jewish code of law (Shulkhan Aruch) in 1722-1723.

This edition included a series of imaginary figures of illustrious medieval rabbis such as Rashi, Maimonides and Ramah on the frontispiece, causing a scandal and postponing a similar reproduction for generations. From the 1770s, Rabbi Jacob Saraval opened Mantua to the new intellectual circles and ideas of Haskala; his translation and edition of Mendelssohn’s Fedone, appeared in Venice in 1806. Among Saraval’s pupils at the rabbinical academy of Mantua, was Benedetto Frizzi (1756-1844) doctor, intellectual and prolific writer, and one of the most eloquent representatives of the Jewish Enlightenment in Italy.

As part of the Austrian Empire, Mantua’s Jewish community underwent the legal and social transformations of the Austrian Jewish emancipation, with an unstable equilibrium between individual and communal rights. By 1791, the emperor Leopold had granted Mantuan Jewry legal equality together with the possibility of buying houses in and outside the ghetto.

Although not all restrictions were abolished, the Austrian reform in favor of Jews continued during the French and Napoleonic eras. During French rule, the ghetto was abolished. Abraham Vita de Cologna, Chief Rabbi of Mantua, became a member of the Napoleonic Sanhedrin. The Jews of Mantua, like their coreligionists elsewhere in Italy, took an active part in the Italian Risorgimento. Giuseppe Finzi sat in the Italian Parliament.

French occupation had negative consequences for businesses with an increase of taxes, but the French brought new concepts of citizenship, rights and regeneration which after the Restoration conflicted with the new attitude of the restored Austrian regime.

With the Congress of Vienna, Mantua returned to the Habsburg Empire, which re-established restrictions on Jews. Jews could, however, possess property; in 1821 the majority lived and worked in the ghetto, but 247 lived in other zones, a sign that they felt relatively safe to live outside.

In 1825, a Jewish philanthropic vocational school was established which became the model for other Italian Jewish communities: dozens of poor children were trained in various ‘mestieri,’ in line with the conception of the time which linked cultural, moral and professional ‘regeneration’ to the aim of rendering the Jews worthy of emancipation.

The anti-Jewish restrictions in Mantua together with local anti-Jewish riots, such as those in 1842, pushed young intellectuals towards new liberal ideas of the Risorgimento; only when Mantua became part of Italy in 1866 were Jews fully emancipated.

Marco Mortara (1815-1894) was rabbi of Mantua from 1842-1894 and dedicated his life to the local issues of the community. Typical of his times he thought of Judaism as only a religious phenomenon with no national connotations; among the orthodox Italian rabbis, he was one of the most in favor of moderate reform.

In 1857, there were 2,298 Jews in Mantua. From 1859, when Lombardy, excluding Mantua, was annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia, many of the wealthiest members of the community left the city mainly to the more economically dynamic and bourgeois city of Milan. Among them the Liberal senator, writer, painter and philanthropist Tullo Massarani, active in politics and a strenuous supporter of women’s education, and Moise Loria, an entrepreneur who made his fortune in Alexandria in Egypt then moved to Milan, where his donations supported the creation of Societa‘ Umanitaria, an important secular philanthropic institution which still exists.

The Jews of Mantua, like their coreligionists elsewhere in Italy, took an active part in the Italian Risorgimento. Giuseppe Finzi sat in the Italian Parliament.

In 1866, the Jewish population in Mantua reached 2,795. In 1872, some commercial sectors were still in Jewish hands, but at the same time the new generations were moving towards the liberal professions as engineers and lawyers.

The migrations had halved and impoverished the community; the area of the ghetto was progressively abandoned, with only the poorest of the population remaining. Between 1894 and 1904, the ghetto began to be demolished.

In 1901, Mantua had lost nearly half of its residents, with only 1,093 Jews affiliated with the community. In 1930, there were 500 Jews living in Mantua. This decreasing trend continued in the years of persecution and deportations from 1938 to 1945 and after World War II. During World War II, over 50 Jews were deported to the death camps or killed. Today, fewer than 100 Jews live in Mantua. The Jewish community of Mantua enters yet another challenge in keeping alive its centuries-old history.