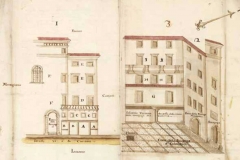

In 1516, Venice’s ruling council confined all the Jews in a small area not far from today’s train station, where there had been getti, or foundries. The gates were locked at night, and restrictions were placed on Jewish economic activities. Jews were only allowed to operate pawn shops and lend money, trade in textiles, and practice medicine.

They were permitted to rent, but not to own real estate. Although restrictive, the Ghetto also provided a safe haven for Jews from the violence and aggression against non-Christians in the economically and politically strained Venice of the early sixteenth century. Despite these severe limitations, the Jewish community prospered in Venice, receiving better treatment there than in many other European cities at this time.

They were allowed to leave the Ghetto during the day, but were marked as Jews. Men wore a yellow circle stitched on the left shoulder of their cloaks or jackets, while women wore a yellow scarf. Later on, the men’s circle became a yellow beret and, still later, a red one.

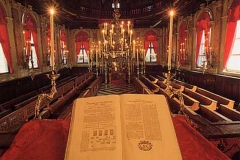

The first Jews to settle in the Ghetto were the central European Ashkenazim who settled in the Ghetto Novo. They built two Synagogues. The Scola Grande Tedesca in 1528-29 and the Scola Canton in 1531-32.

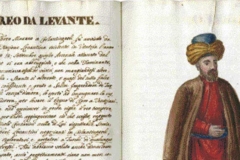

Next came the Levantine Jews, who practiced the Sepharadic rite. When they got their own neighborhood, the Ghetto Vecchio, an extension of the Venetian Ghetto granted in 1541, they built the Levantine Synagogue.

Mixed in with the poorer Ashkenazim were Italian Jews who had migrated north to Venice from central and southern Italy. In 1575, they built their own Italian Synagogue.

In 1633, the Ghetto Novissimo was built to house twenty Sephardic families. Over the years the number of scole in the Ghetto increased to nine, of which five survive today.

Levantines and Ashkenazim, Italian and Spanish Jews all lived together in the Ghetto through hard times – including the plague of 1630 – and better times, until Napoleon threw open the gates in 1797 and recognized equal rights to the Jews of Venice. At its height, around 1650, the Ghetto housed about 4,000 people in a space roughly equivalent to 2-1/2 city blocks. Before World War II, there were still about 1,300 Jews in the Ghetto, but 289 were deported by the Nazis and only seven returned.

The Jews of Venice

The first Venetian document, so far as we know, in which Jews are mentioned is a decree of the Senate dated to 945, prohibiting captains of ships sailing in Oriental waters from taking on board Jews or other merchants – a protectionist measure which was hardly ever enforced.

According to a census of the city said to have been taken in 1152, the Jews in Venice numbered 1,300, an estimate which Galliccioli himself believes to be excessive. An event which must have increased the number of Jews in Venice was the conquest of Constantinople by the allied Venetians and French in 1204, when the former took possession of several islands in the Levant, including Eubœa, where the Jews were numerous. At that time, Jewish merchants went to Venice for the transaction of business, with some of them settling there permanently.

The first lasting settlement of Jews was not in the city itself, but on the neighboring island of Spinalunga, which was called “Giudeca” in a document dated 1252. For some unknown reason this island was afterward abandoned.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, some Jews went to Venice from Germany, some seeking refuge from persecution, others attracted by the commercial advantages of this important seaport. A decree of the Senate, dated 1290, imposed upon the Jews of Venice a duty of 5 per cent on both imports and exports. R. Simeon Luzzatto (1580-1663) speaks in his noteworthy “Discorso Circa il Stato degli Hebrei di Venetia” of the Jew who was instrumental in bringing the commerce of the Levant to Venice.

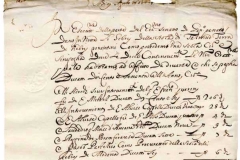

An ordinance of 1541, issued by the Senate on the advice of the Board of Commerce, to provide Jewish merchants with storehouses within the precincts of the ghetto, observes that “the greater part of the commerce coming from Upper and Lower Rumania is controlled by itinerant Jewish Levantine merchants”.

When the “Cattaveri” were commissioned in 1688 to compile new laws for the Jews, the Senate demanded that “the utmost encouragement possible should be given to those nations [referring to the various sections into which the whole Jewish community was divided] for the sake of the important advantages which will thus accrue to our customs duties”.

The right of the Jews to reside in Venice always remained precarious. Their legal position was not regulated by law, but was determined, as in the case of other foreign colonies, by “condotte” granted for terms of years, and the renewal of which was sometimes refused. The Jews, indeed, were twice expelled and compelled to retire to Mestre.

Although Jews were allowed to conduct business in Venice throughout the 14th century, they were not permitted to remain the city for more than fifteen days at a a time, and in 1434, they were obliged to wear a badge. While the restriction to fifteen days’ residence does not seem to have been enforced long, other repressive measures followed: schools for games, singing, dancing, and other accomplishments (“di qualsiasi dottrina”) were prohibited, and so was all association with Christian women. Professions, except for medicine were also prohibited.

In the second half of the 15th century, the Jews of the entire republic were menaced by the clerical agitation against Jewish money-lenders.

A much more serious fate befell the Jews of Trent when the monk Bernardino da Feltre accused them of the murder of a Christian child (1475). Although the Doge of Venice, Mocenigo, issued a strong manifesto for the protection of the Jews, he could not prevent a similar trial for ritual murder from taking place in Venice itself a few years later, attended by the same atrocious methods of procedure.

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1496) brought many exiles to Venice, and among them came, after many peregrinations, the celebrated Isaac Abravanel, who, during his residence in Venice, had occasion to use his diplomatic skill in settling certain difficulties between the republic and the King of Portugal.

Times of peril now followed for the republic. In 1508, nearly all of the states of Europe, including Austria, France, Spain, the Papal States, and Naples, united in the League of Cambray against the Serenissima. The common danger had the effect of relaxing the enforcement of the anti-Jewish laws and of drawing Jews and Christians together in more friendly relations.

Jews from various areas sought protection in Venice. Jews began to arrive in the city joining other minorities to which the government had assigned areas of residence. However, for the Jews a further measure was established: they were given a segregated area, enclosed by walls and gates and shut down at night, in which the contact with Christians would be limited. The first ghetto was born.

Synagogues, formerly scattered throughout the city, were now permitted only in Mestre, but before long a new concession allowed them in Venice again, though only in the ghetto.

The settlement of Jews in Venice brought along not only economic advantages to the Republic, but made Venice one of the most important centers of Hebrew printing in Europe. Although Jews, with a few exceptions, were not allowed to own printing presses, Christian printers invested in Venice and gave birth to the modern Jewish canon. Daniel Bomberg, among them, published some of the most important works of rabbinical literature.

Humanism had sparked interest in new ways to read the Scriptures, in the culture and traditions of the Jews, as well as in the Hebrew language. The possibility of large production of volumes created enthusiasm as both Jews and Christians had an interest in commissioning books. Printing however, created new challenges: on one side it changed the attitudes of rulers, especially the Papacy, towards Jewish knowledge which was becoming more widely available and, in their eyes, more dangerous. It also affected the Jewish world, which suddenly had to confront the issue of textual authority on a completely different scale. Systems of internal control were established both to curb the Church’s reactions as well as to guarantee a unity of visions and traditions that up to that point had allowed for a wide range of versions. If on one side the press expanded Judaism’s reach, on the other, it forced it to adopt normative canons and restrict its practices.

In 1553, however, the proscription of Hebrew literature by the Inquisition began, and all copies of the Talmud which could be found in Rome, Venice, Padua, and other cities were confiscated and burned.

In 1527, another expulsion took place, although it probably affected only the money-lenders, who withdrew to Mestre, but were permitted to return to Venice for the time necessary to sell their pledges. In 1534, they were called back, and this time the Jews organized themselves into a corporation called “Università.”

Since each man wished to preserve his own nationality according to the country from which he came, the Università was divided into three national sections, Levantines, Germans, and Occidentals, the last name being applied to those who came from Spain and Portugal. The administration of the whole Università was in the hands of a council of seven members, three chosen from the Levantines, three from the Germans, and one from the Occidentals. Many laws were passed, furthermore, to regulate the whole internal administration of the community. According to Schiavi, an internal tribunal was also established to adjudicate both civil and criminal suits, but later on the Council of Ten limited its powers to civil suits and, in these, it could act only when the parties appealed to it.

The most powerful weapon of which the heads of the community could avail themselves was that of excommunication, although it appears that legally at least the exercise of it was not left wholly in Jewish hands.

Galliccioli records at length a successful appeal presented to the Patriarch of Venice by the heads of the Università, for permission to excommunicate those living in the ghetto who neglected their religious duties; and the author adds that the right to give this authority had been in the hands of the patriarch until 1671, when it passed to the “Cattaveri”. It does not appear, however, from any subsequent documents that the Jews held strictly to this dependence.

Schools for study were naturally among the most important institutions of Jewish life in Venice at all times. In addition to Hebrew, they cultivated secular knowledge.

Although restricted to the ghetto, the Jews moved throughout the city. In the 16th century, when gambling raged in Venice, it also affected the ghetto and Jews and Christians often played together. Although the government had already imposed penalties upon gambling, the heads of the Università saw that the measure remained ineffective, and they pronounced excommunications in the synagogue against those who played certain games.

Excommunication failed. Leon of Modena, whose reputation was seriously stained because of his addiction to gambling, wrote a long protest against his own excommunication, which he declared illegal; the ban, he said, only drove people to worse sins. In all his long discussion, there is no sign of the fact that the pronouncing of the excommunication was dependent on any but the Jews themselves. It appears from the disquisition of Leon of Modena that the number of Jews then in Venice was little more than 2,000, although some scholar think the number was higher. According to a census from 1659 4,860 lived in Venice.

Many Jewish societies and confraternities were active in Venice including the society for the ransom of Jews who had been taken prisoners, especially Jews who had sailed on Turkish ships from Constantinople and other Oriental ports, and had fallen into the hands of the Knights of St. John, who waged a fierce and continual warfare against such ships.

The Venetian society had a permanent Christian delegate on the island of Malta, whose duty it was to alleviate the lot of the wretched captives as far as possible and to conduct negotiations for their ransom.

In 1571, after the battle of Lepanto, in which the Venetians and Spaniards conquered the Turks in the contest for the island of Cyprus, the danger of expulsion returned to threaten the Jews of Venice. During this war, much ill feeling had arisen in Venice against the Jews because one of their coreligionists, Joseph Nasi, was said to have suggested the war, and many Venetians suspected that the Jews of the city had sympathized with him.

After the victory, the Senate ordered the end of the “condotta,” within two years when all Jews should leave the city. This decree, however, was later revoked.

In 1572, Sultan Salim II sent the rabbi Solomon Ashkenazi, who, both as a physician and as a statesman, possessed great influence with the Divan, as a special ambassador to the Senate, charged with a secret mission to conclude an offensive and defensive alliance between the two states against Spain. The Senate received him with all the honors due the ambassador of a great power, and, although it did not accede to his proposals, it sent him back with presents. Ashkenazi availed himself of this opportunity to defend the cause of his coreligionists, and he seems to have obtained not only the revocation of the decree of expulsion, but also the promise that such expulsions should never again be proposed.

While the administration of the Venetian republic was always under papal influence, a spirit of comparative tolerance prevailed there, and the Jews, like other minorities, including the Germans, the Greeks, the Albanians and the Turks, were free from restrictions in their worship.

Well organized and strong, the republic always maintained order. The “condotte” were religiously observed, and the lives and property of Jews were protected. Local outbreaks against the Jews were of rare occurrence and were quickly followed by exemplary punishments. The Inquisition existed at Venice, although it was not admitted until 1279, after long opposition, but its jurisdiction extended only over Christian heretics, and even over them its power was much restricted.

Nevertheless, the Venetian tribunal maintained strict control and censorship over the Jews and other groups.

In 1553, the council granted Kalonymus, a Jewish physician, the means necessary to keep his son at his studies, “so that he may become a man useful in the service of this illustrious city”. In the great financial stress in which the republic was placed during the long and expensive war with the Turks, heavy taxes were imposed on the Jews.

Most important of all was the activity of the Jews in maritime commerce. In 1579, in the interest of this commerce, permission was extended to many Jews of Spanish and Portuguese extraction to move from Dalmatia to Venice, where they received privileges which were obtained for them by their coreligionist Daniel Rodriguez, who was then Venetian consul in Dalmatia, and who was highly esteemed by the republic for his important services in furthering its commerce in the Orient.

Naturally, this maritime commerce continued to be favored by the government and, in 1686, the Portuguese Aronne Uziel was the first to obtain a patent for free commerce under the Venetian flag in the Orient and Occident. He was one of the first shipowners of the republic; he traded with Zante, Cephalonia, Corfu, and Constantinople and his business was so great that in twenty years he paid 451,000 ducats to Venice in duties.

Among other Jewish shipowners one of the most important was Abramo Franco, whose duty it was to provide for the loading of six merchantmen. To come down to more recent times, special mention should be made of the two brothers Baron Giuseppe Treves dei Bonfil, the ancestor of the present barons of that name, and Isaaco Treves, on account of the expedition which they undertook for the first time into the western hemisphere. They sailed under the Venetian flag with a cargo of flour and other goods, returning with coffee and sugar. Giuseppe Treves received the title of baron from Napoleon I on account of his great services to the city, both commercially and otherwise.

Domestic trade continued to be limited legally to second-hand goods, but, as a matter of fact, this nominal restriction counted for little and, with the growth of the city, liberty of trade grew also. In the shops of the ghetto wares of all sorts were sold, among them: glass, decorated crystal, gold ornaments, tapestries, embroideries, and books. A trade of special importance, against which ineffectual prohibitions were several times issued, was that in precious stones; the sovereigns of Europe were the first to employ Jews for selling, buying, and exchanging gems. Jews were prominent also in engineering. In 1444, a decree of the Senate called “a certain Solomon, a Hebrew by race, to be present at conferences concerning the diversion of the Brenta, because he has great fame for skill in matters concerning water”.

In 1490, an engineer, wishing to associate himself with some Jews in the mounting of a machine which he had invented, asked the Senate whether the laws concerning the granting of privileges to inventors were applicable to Jews as well as to others. To this the Senate replied that in such matters no distinction was made between Venetians and foreigners, between Jews and Christians. One Ẓarfati, in the second half of the 16th century, invented certain improvements in the methods of silk-weaving, and his studies were published at Rome and obtained for him a privilege from Pope Sixtus V. In 1630, a certain Naḥman Judah obtained permission to manufacture cinnabar, sublimate, and similar compounds, on condition that the business should be carried on under the name of a Christian. In 1718, another Ẓarfati was permitted to manufacture not only cinnabar and sublimate, but also aqua fortis, white lead, minium, etc.

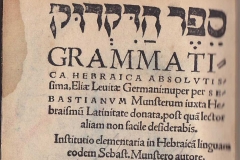

In spite of restrictions, writing also flourished among the Jews. Grammarian Elijah Levita, who spent a great part of his life in Venice. Noteworthy also were the two rabbis already mentioned, Leon Modena (1579-1649), at whose sermons even nobles and ecclesiastics were present, and Simeon (Simḥah) Luzzatto (1590-1663), who, besides the “Discorso,” wrote “Socrate, Ossia dell’ Intendimento Humano,” which he dedicated to the doge and Senate.

Reference should also be made to the poetess Sara Copia Sullam (1592-1641), who was regarded by several critics as one of the most illustrious writers of verse in Italy. Other authors of this period who wrote in Hebrew were: David Nieto (1654-1728), author of the “Maṭṭeh Dan”; Moses Gentili (d. 1711), author of “Meleket Maḥshabot”; his son Gershon, author of the “Yad Ḥaruzim”; Rabbi Simeon Judah Perez; and Jacob Caravel.

One of the conditions always imposed upon the Jews of Venice was that of keeping banks for lending money; to insure their continuance the “condotta” of 1534 placed this obligation upon the Università as a body. Although these banks at first satisfied the requirements of the citizens and were, at the same time, a source of gain to those who kept them, they finally ended in a great financial disaster.

The community, which initially was very rich, declined rapidly during and after the war with the Turks over the island of Candia (1645-55); the cause being the enormous burdens laid upon it by the expenses of the war. Many emigrated to escape these burdens. The plague of 1630, with the consequent stagnation of business, drove others out. Bad administration was responsible for other departures. So, in order to fulfill its obligations, the community was forced to sink deeper and deeper into debt, which finally reached the sum of nearly a million ducats.

As soon as the government saw the peril of an institution which was considered a necessity to the state, it endeavored to remedy the evil by adopting more favorable terms of payment and by making other arrangements within its leaders. Eventually, the Università was proclaimed a private corporation and enabled to legally announce its insolvency. In 1735, the Università suspended payments and a compromise was effected with its creditors with the support and protection of the government. The banks continued to exist, however, even after the fall of the republic until 1806, when they were closed by an imperial decree.

On that occasion the Jews gave the commune all the money and property in the banks, having a total value of 13,000 ducats, to be devoted solely to charity. The municipality publicly expressed its gratitude for this gift (“Gazetta di Venezia,” Oct. 6, 1806).

The Università recovered from its bankruptcy. In 1776, on the expiration of one of the “condotte,” certain commercial restrictions were proposed as a check upon the excessive influence which the Jews had acquired. These proposals gave rise to many heated discussions. The majority sided with the Jews and called attention to the fact that several Jewish families had acquired large fortunes by their thrift and were, hence, of service to industry, besides giving employment to many of the poor. The assistance they had rendered to the state was also called upon, special emphasis being laid upon the noble conduct of Treves, who had loaned the treasury without interest the money necessary for the execution of the treaty of Barbary. After a long debate, however, the passions and influence of a few powerful reactionaries prevailed, and the proposals became law.

Under pressure from the Napoleonic wars, the Republic declared all citizens equal and all legal discrimination against the Jews became null. Each strove to outdo the other in demonstrating his fraternity, and on July 11, 1797, amid great popular rejoicing, the gates of the ghetto were torn down and its name changed to “Contrada dall’ Unione”. Many speeches of lofty tone were made on this occasion, and even priests were present at the ceremony, setting the example of fraternity, for which they were praised by the new municipality. The latter had been quickly constituted, and three Jews had at once taken their places in it.

Yet even this revolution, though made in the spirit of the times, could not save the republic, which was powerless before the invading armies of France. In the very month in which this change of government took place, Napoleon declared war on Venice and the Senate, wishing at least to make an attempt at resistance, invited the Jews and the various religious corporations of the city to contribute all the available silver in their places of worship for the defense of the city against the impending attack.

The Jews responded to this appeal. The attack, however, was never carried out. The Senate abandoned the Republic on Oct. 17, 1797 and Austria and France signed the treaty of Campo Formio, by which the city was assigned to Austria.

The latter took possession in 1798. The Jews lost again their civil equality. They regained it in 1805, when the city became a part of Italy, but lost it once more in 1814, when, on the fall of Napoleon, the city again came under Austrian control.

When the news of the revolution in Vienna reached Venice in 1848, the city seized the opportunity to revolt and, almost without bloodshed, forced the Austrian garrison to capitulate in 1848. It then proclaimed anew the republic of Saint Mark and elected a provisional government, of which two Jews formed a part — Isaaco Pesaro Maurogonato (appointed to the Ministry of Finance) and Leone Pincherle. Austria, however, reconquered the territory and held it until 1866, when it became part of the united kingdom of Italy. From that time the complete equality of Jews and Christians has been firmly established, as had happened in the rest of the country with the exception of Rome.

In unified Italy, Venetian Jews distinguished themselves in all fields: Samuel Romanin, the learned historian of Venice; Luigi Luzzatti, who was prime minister and minister of the treasury; the Treves dei Bonfili family, whose members still continue, as in the time of the republic, to be distinguished for their philanthropy and for their services to their fellow citizens; the poetess Eugenia Pavia Gentilomo Fortis; the physicians Namias and Asson; and the rabbi Abramo Lattes. In the industrial field the Venetian Jews were also well represented, being interested in many of the numerous factories and establishments on the islands around Venice, either as proprietors or as managers. Playwright and political activist Amelia Pincherle Rosselli was also of Venetian origin.

More complex is the analysis of the Jewish society during the fascist period. A well-known figure, Margherita Grassing Sarfatti became central to the shaping of Italian culture as well as of Mussolini’s international image. The rapid changes and the contradictions of the early 20th century as well as the reactionary wave in the relation between Church and State placed the Italian Jews in a precarious situation causing abjures, conversions and departures. The Venetian community shrank from over 2,000 members to 1,800 in 1931 and 1,200 in 1938. Between December 1943 and August 1944 over a third of the Jews who were in Venice were arrested and deported. After the war, barely 1,000 remained in the city.

Today, in spite of the small Jewish population, Venice is a subject of study and a destination for many scholars interested in the important culture that was formed there, as well as to understand the circumstances in which the first ghetto was created, ratifying in legal terms a relation between ruling power and minority that shaped all subsequent occurrences.

Source: Encyclopedia Judaica